How Can Our Culture Escape the Trap of Mom Rage?

Here’s why mom rage IS about the larger social structures, and why shame is never the answer.

When I started this newsletter almost 2 years ago, it was a messy sandbox of my thoughts about trying to parent my neurodivergent kid mindfully in an ableist world.

As the community has grown, especially when

recommended us, I’ve worried more about writing the “right kind of content,” even though I know that sharing my truth with you is the most healing for both of us.I’ve held this post back for weeks, and I don’t regret that. I don’t like to post when I’m triggered, but this topic pushes my buttons every minute of every day, so here goes.

This is the only way I know to be helpful right now. The othering and dehumanization happening inside ourselves fuels the worldwide othering and dehumanizing. They are not separate. When we turn our rage on ourselves, there’s a generational cost to that, too.

The rage festers and we are left under a pile of loneliness and debilitating shame… The shame is as bad as the rage and just as damaging.

-Minna Dubin

If I know you at all, I know you’ll either shout from the rooftops or unsubscribe, and I understand. You get to choose what enters your inbox. If you wish to shout it:

Disclaimers:

This is a heteronormative, cisgendered post. I’m not skillful enough to write it in another way yet. I’ve been swimming in the soup of misogyny all my life, and I’m a mom with a lot of baggage, and apologize in advance for the harm I’ll cause.

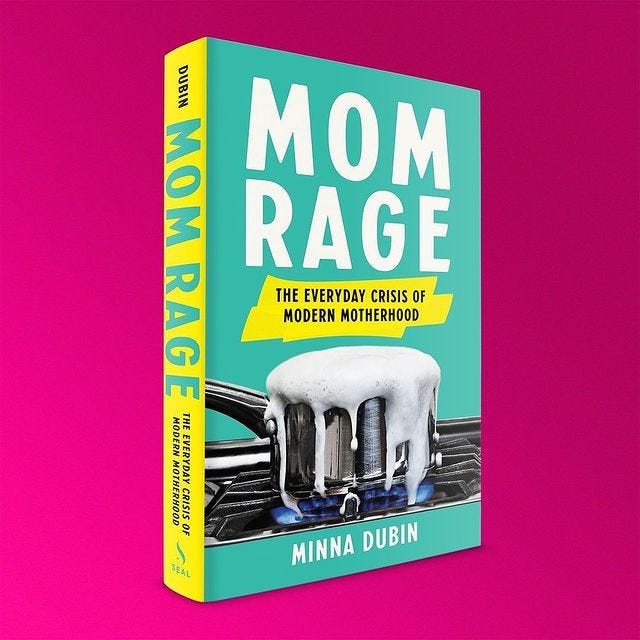

I haven’t read the book yet. “Mom Rage: The Everyday Crisis of Modern Motherhood” by Minna Dubin is on my short list.

I have devoured her essays, though. Minna’s original NY Times article, “The Rage Mothers Don’t Talk About” and her pandemic follow-up, helped me feel less alone when I was losing my shit in 2020.

Dubin writes, “We feel the need to qualify our frustration with ‘I love my child to the moon and back, but….’ As if mother rage equals a lack of love…”

My breath catches, because finally someone is speaking the truth.

If you recognize yourself in these words, you’re not alone. Paige Bellenbaum, founding director of The Motherhood Center, said, “Mom rage is something we talk about all the time. Social isolation, lack of support, managing high levels of anxiety and stress — this is the new normal of being a mother.”

Dubin quotes Ann Lamott’s article, “Mother rage: theory and practice;” “All mothers have it. No one talks about it. That only makes it worse.” You mean we’re not alone?

What a relief!

For most of us raised as girls, there has never been room for our anger. We were taught by our own mothers to apply shame as a stopper to push it down. It was passed down unconsciously, of course, as survival skills often are.

Then, when when we grew up and became parents, and things got hard (sometimes really hard), we discovered that the rage was still there, unfamiliar and scary because we had never dealt with it.

…the myth of maternal bliss is so sacrosanct that we can't even admit these feelings to ourselves.

-Ann Lamott

There’s so much stigma around mom rage that many moms wouldn’t go on record to be interviewed by Dubin. A few people are finally speaking openly about their rage. What causes mom rage? Our own inner critics, unsustainable labor inequality, and misogynist societal expectations have created a pressure cooker ready to blow.

Which is why I was enraged on so many levels by Merve Emre’s reactionary New Yorker review, “What is Mom Rage Actually?”

In the print edition, the review is called “The Mother Trap” which is apt, as that’s what has already been happening in this culture. We feel trapped by the confines of patriarchal inequity. Emre contributes her own strands to that web; trying to put us back in our places by wielding a misguided misunderstanding of rage and shame.

“Dubin’s presupposition is that it is desirable to banish shame from the scene of parenting… surely this depends on the cause of shame…”

-Merve Emre

No.

It doesn’t depend on the cause of shame.

Shame drives those who are already isolated deeper underground. It’s dangerous to heap shame on top of whatever a struggling parent is already going through. When we create safety for parents, and space for all emotions, there’s no place for shame.

Repair can only happen when we are willing to turn toward self-acceptance, self-inquiry, self-compassion, and connection. There is a time for guilt, for sure, and when we feel supported and accepted, we can unpack our guilt and learn from it.

Emre seems to have no understanding of how rage or shame are healed. We must believe in our ability to change. We need to believe we are inherently good. It’s how we will do better.

I listened to a podcast interview in which Emre pointed the finger of ‘moral cliché’ in an astonishingly condescending way, especially for someone who sees parenthood as “a series of ethical challenges.”

She says, “You have to rise to the occasion of being a conscientious parent… There are people who… turn parenting into a very deliberate kind of ethical project.” Emre believes that parenting has little to do with capitalist patriarchy, and instead moralizes that parenting should be an “ethical project” because “it takes great will and self-understanding to break patterns.”

“In my mind it’s more about a set of interpersonal feelings like shame and anger and frustration, not primarily (and maybe not even secondarily) about these larger social structures.” (I’m guessing that Emre meant intrapersonal rather than interpersonal.)

But breaking patterns can never stop at the intrapersonal OR the interpersonal level of society. Change must break down systemic failures, and rebuild social structures so they are more supportive.

Emre’s statement that “Under patriarchy, under capitalism, everyone is exploited. it’s not just women, it’s men as well.” smacks of “All lives matter.” It’s dismissive of a very real systemic inequity, that will not be resolved by a single mother simply deciding to be a more ethical person and pulling up her bootstraps. Anyone who thinks “‘white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy’ doesn’t continue to shape the conditions of contemporary motherhood in profoundly unjust ways” is living under a rock.

Emre’s thesis is that it’s important for parents to feel shame!

She quotes “rarified queer theorist” Eve Sedgwick and her work on shame, but never once mentions the more recent and comprehensive shame research by Brené Brown:

“I define shame as the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love and belonging—something we’ve experienced, done, or failed to do makes us unworthy of connection.

“I don’t believe shame is helpful or productive. In fact, I think shame is much more likely to be the source of destructive, hurtful behavior than the solution or cure. I think the fear of disconnection can make us dangerous.”

-Brené Brown

Emre shows a core misunderstanding here about the effect of shame on our ability to repair, connect, and change. Shame is a trauma response.

Emre says in the interview,“I do feel quite frustrated in general reading the motherhood discourse of the past decade or so. I realized how inattentive a great deal of it is to the child. I do think we need to recognize that children are people.”

OF COURSE children are people!!!

This child-centered moralizing and inattention to mothers’ needs is exactly how we got to this collective place of primal scream in the first place!

Children’s wants and needs have been so centered in our culture that most mothers I know cannot identify their own needs. Having any needs at is taboo. Never mind wants. But ALL humans have basic human needs. Yes, even moms, no matter how hard we deny them!

Resentment arises when our boundaries are crossed. If someone doesn’t know that they have needs, how will they know where their boundaries lie?

Emre equates rage to power, but it is the lack of power that fuels rage in moms who are overburdened and unheard. Rage is not intentionally directed toward children, or toward anyone. It bubbles from within, and whoever is most proximal will feel its sting.

She points to “higher rates of abuse of children” explaining that capitalism, patriarchy, and injustice “do not necessarily mean you get a blank check on your treatment of others.”

“Parents who do that to their children do it because they can get away with it.”

No. Absolutely not.

Parents who do that feel immense shame. This misconception only snowballs that shame until the parent hides their struggles - feeling like a monster - dehumanized. From that dark place there’s no hope that they can do better.

Monsters don’t change. But humans can always change.

Wanting moms to feel MORE SHAME is not going to help anyone, especially not children. When moms are valued, children do well.

When we humanize, normalize, and reframe these struggles as a cultural issue, parents see that they aren’t the only ones, that their rage is a more universal issue than they have been led to believe, that they ARE GOOD, and that even if they have done something they feel guilty about, there is room to change.

Emre talks of “mechanisms of social surveillance” being what keeps mothers from abusing their kids, as if we were just waiting for a secret moment away from prying eyes to do bad things. What a horrifying assumption! She says the pandemic “made it easier for parents to abuse their children.” Does Emre believe we would all abuse our kids if nobody was looking? It is never “easy” for a parent to abuse their children.

It isn’t the lack of “mechanisms of social surveillance,” but the lack of mechanisms of social SUPPORT that were plucked away during the pandemic which led to upticks in abuse.

No one is excusing abuse, but that doesn’t mean shame is the solution.

Emre says, “I think it is really important to feel shame… shame is what allows us to see or to feel the reality of other human beings… in parenting it is one of the most powerful ways to feel that… it is a way for you to recognize that other person and recognize your responsibility to… that other person. To want to evade that is… the essence of cruelty.”

“It’s also an invitation to make that relationship anew.” How is shame an invitation to repair a relationship? Emre seems to have no understanding of how rage or shame actually work.

Guilt: I’m sorry. I made a mistake.

Shame: I’m sorry. I am a mistake.

-Brené Brown

Here’s why mom rage IS about the larger social structures:

We don’t have the time, energy, or permission to explore and work through our complicated feelings. They get pushed down, or bottled up because there’s no space in our culture for moms to have these unattractive feelings. Parenting in this culture is already ALL about the kids.

Shame is the driving force in behaviorist parenting models. The latest neuroscience shows that has not gone well. When people feel shame, there’s no drive to change because we don’t see ourselves as worthy.

To bolster her points, Emre refers to Mother rage: theory and practice by Ann Lamott. Funnily, Emre’s theory that shame is helpful directly contradicts Lamott’s: “All mothers have it. No one talks about it. That only makes it worse.” “Good therapy helps. Good friends help. Pretending that we are doing better than we are doesn't. Shame doesn't. Being heard does.”

When Lamott’s friend shared a story of parental rage with her, she wrote, “I love that he told me about it when I was in despair about a recent rage at Sam. Because, while I'm not sure what the solution is, I know that what doesn't help is the terrible feeling of isolation, the fear that everyone else is doing better.”

Lamott, in her humility and empathy, offers to help those who realize they have gone over the line. “…we know how you must have felt right before it happened.”

And Lamott explains precisely why systemic oppression contributes to our inability to live up to our standards all the time. There are so many demands on us that by the time we’re triggered by our kid: “You're at high idle already, but you are not even aware of how vulnerable and disrespected you already feel.”

While Lamott and Dubbin write vulnerably of their shame, their guilt, their failings as mothers and try to figure out what to do about it, Emre hides. She tells a story about her children which exposes nothing of her own flaws. I suspect we’re not getting the full picture, and the trust she describes feels hollow and condescending. “Nobody is perfect but I do think we would benefit from being a tiny bit more mindful of what we model.”

Emre grasps at moral high ground when she judges those who write about their kids, then later in the same interview tells the story of her kids breaking a neighbor’s window while playing ball. Her child expressed shame. When he was literally hiding his face and saying he was ashamed, she told him, “You have nothing at all to be ashamed of, because accidents happen.” What is Emre saying? Does learning from shame apply to her child, or does it not? She lists virtues - responsibility, honesty, repair - as the outcome of his shame. But those are fruits of guilt and connection.

In the New Yorker review, Emre argued that Dubin’s experience is not relatable because her kid is autistic.

As a parent of an autistic kid, I see us as canaries in the coal mine. It’s coming for everyone, we just feel it first. If it hasn’t come for you yet, wait… or help us change the system!

When you have an autistic kid, you may not even have time to catch your breath. Most parents I know are just trying to survive. What are they trying to survive? THE SYSTEM. A special education system built as a gatekeeper to maintain a bottom-of-the-barrel budget, because our culture doesn’t value disabled people.

In the lives of parents fighting these odds, rage is the fuel that gets the short bus arriving on time, dials dozens of pharmacies searching for necessary medication, advocates for their kids’ rights all day long. Emre’s prescription of “great will and understanding” gets used up by the third meltdown of the morning. Rage can provide helpful energy to fight for our kids. Just because a mom has rage, doesn’t mean she’s contriving to abuse her child. In fact, she’s much more likely using it to fight injustice.

As accomplished a journalist as Emre is, it makes me wonder how often she looks in the mirror.

Dubin, trying to do better, joined an “anger-management group for mothers…

“The most important part, for me, is the mirror provided by the circle of tired, sad mothers… Another mom admits that she wants to throw her child across the room, and the rest of us have forgiven her before she has finished her sentence. We all nod, as our bodies flood with relief that the rage has not singled us out.”

-Minna Dubin

Dubin writes, “I have not yet found the golden ticket to serenity, but I have noticed that when I manage to exercise, make art and eat healthy food, I have a longer fuse.”

Patriarchy and capitalism contribute to the downward spiral of mom rage because there is a cultural expectation that moms set our basic needs aside, which is not just unfair but impossible. If we’re socialized as girls we begin training to deny our needs very young. If we can’t, we feel faulty. If we push back, our basic need for connection is denied.

When our society’s systems change to favor moms, protecting our space to rest, breathe, move, recharge, self-reflect, create, eat nourishing food from our own plates… acknowledge our basic human needs…

When that happens, it will be a better world for everyone. Especially the children.

“Eating properly, exercising, showering and getting a little alone time sound like they belong in the ‘basic health requirements’ category as opposed to ‘self-care for mothers.’”

-Minna Dubin

Thank you for this thoughtful article on something that has been a secret for so many of us for too long. It comes as a relief to see it all in the open.

Noticed Jeff's comment... I have heard the things you mention come out of my own mouth. Sometimes because the programing and spaces available to my children have been grossly underfunded with poorly trained staff. Sometimes because we have made it so easy to abuse disabled children that I have had to in order to keep my children with limited vocabulary, and thus unable to report, safe from harm. And yes, sometimes I have said these types of things because I simply cannot manage parenting, being a development and behavioral specialist, a foster care case worker and a decent loving warm mama and I was so terrified by the systems failing my child that I couldn't trust anyone. So stuck in between and rock and a hard horrible place and isolated and shamed for being so -- how could I figure that all out and be socially graceful too! I couldn't. And that is exactly why I find this article so important. It gives me hope that not doing it alone could also mean not blindly over to anyone who will take them because I haven't the energy to do any better.

I think it's so important to acknowledge that anger was not allowed for those of us raised as girls. Well, feeling it was OK. Expressing it was not allowed! We were trained to cry when we were mad, less threatening to the men in our lives. When I was fifteen I was so frustrated that, when my father came home on Sundays he was treated like a king. We put on our party dresses and he sat in a big chair and we brought him food and coffee. Meanwhile my mother mowed the lawn repaired the television and the washing machine cooked all the meals wash all the dishes etc. etc. etc. He was only home on Sundays. He had a lot of other extracurricular activities going on in the city the rest of the time, and of course he "worked." Well, that particular Sunday, my mother was preparing food at he came down and sat in her chair. Symbolically it just made me so mad. Absolutely no support for her, not even much money. She went nine years one time without a new pair of shoes. Meanwhile in the city he was taking taxi cabs and living in hotels., I broke all the taboo in the family and said to him, shaking, "that's my mother's chair." he stood up to his full 6 ft. height and bellowed at me very loud, deep voice, "no Daughter of mine will talk back to me!" I ran upstairs sobbing and of course I never did it again. But I left home when I was 17.